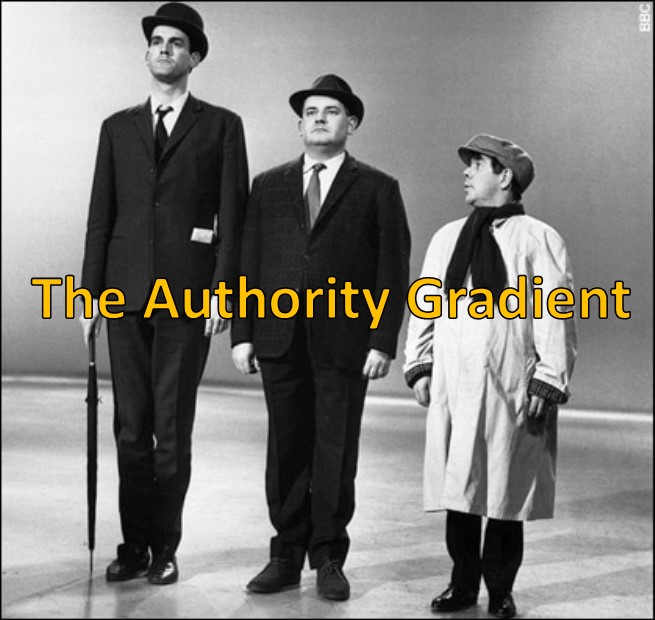

An accidental discovery this weekend led me to a number of articles about the impact of the ‘authority gradient’ in high stress, high stakes situations in both medicine and the airline industry.

The authority gradient is defined as the perceived difference in status between different members of an organisation. It is a barrier to effective communication and a potential source of interpersonal resentment and organisational error. Authority gradients exist in organisations when one member of a team, e.g., a recently qualified first officer, feels he or she cannot broach an important safety issue with another colleague on a higher level, such as an experience airline captain.

Could there be similar dynamics in play in schools and multi-academy trusts which result in poor decisions about around the probity and regularity of a particular course of action. Might inaction by school business professionals in the face of some of the worst excesses of malpractice, be as a result of the authority gradient?

Whilst the pace of action in school strategy and leadership may be slower than in an aircraft or on an operating table, the slow-motion disaster can be just as inevitable.

The difference in the relative authority between academy chief executives and their business managers can be stark. The CEO has hiring and firing authority over the sch biz lead. As a result of legacy behaviour ported across from the maintained sector upon conversion, one holds all the perceived power, status and authority whilst the other is clearly a subordinate.

Authority is not always associated with the competence to use such authority effectively, and it may be denoted by Rank, defined by Role, adopted through Ability and/or appropriated by force of character. In terms of responsibility for decision-making, authority may also be thrust reluctantly onto another person (knowingly or unknowingly) by colleagues who shirk responsibility or feel under-confident.

This leads to problems, as these extracts from the SKYbrary reference website for aviation safety explain:

(Extreme) Steep Authority Gradient

When a team leader has an overbearing, dominant and dictatorial style of management, the team members will experience a steep authority gradient. Team members will view such leaders as overly opinionated, stubborn, and aggressive. When such conditions exist, expressing concerns, questioning decisions, or even simply clarifying instructions will require considerable determination as any comments will often be met with criticism. Team members may then perceive their input as devalued or unwelcome and cease to offer anything; and, in extreme cases, cease to participate completely.

Steep Authority gradients act as barriers to team involvement, reducing the flow of feedback, halting cooperation, and preventing creative ideas for threat analyses and problem solving. Only the most assertive, confident, and sometimes equally dominant team members will feel able to challenge authority. Authoritarian leaders are likely to consider any type of feedback as a challenge and respond aggressively; thereby reinforcing or steepening the gradient further.

Authoritarian leaders are often described as “goal orientated” at the expense of “people orientation”. They may themselves consider that this is the case, but by denying themselves the resources available (skills, knowledge and motivational support of other team members) their actions are self-defeating and goals are less likely to be attained

Does this sound familiar to any SBMs reading this? Can you think of times when you have opted to keep your own counsel in the belief your voice will not be heard?

There is another application of the authority gradient issue described by the authors of SKYbrary which we should bear in mind – that of the shallow authority gradient.

(Extreme) Shallow Authority Gradient

A “paternalistic” leader who only pursues a course of action that has been democratically agreed, following equal opportunity for each and every team member to give input, will have reduced the authority gradient to zero. Decision-making will be extremely slow, and by giving equal opportunities to all, irrespective of experience levels, some of those decisions will be wrong. This in itself can undermine the leader’s authority in the eyes of more experienced team members and possibly lead to their disengagement.

Such circumstances, and subsequent breakdown of communication, may also result in some team members acting independently of the leader. Responsibilities may become blurred.

Where a flat or distributed leadership structure exists or a school leader is OVERLY consultative, problems occur when experienced team members perceive that too great a weight is place on democracy over knowledge/experience. Many SBMs will experience this scenario when issues of finance or regulatory compliance are discussed in SLT meetings with all members of SLT, teaching and non-teaching, allowed to opine equally on the subject. You might think in this ‘land of the blind’, the one-eyed SBM would be king, but an irregular course of action is often selected on the basis of (teacher-led) democracy.

Confusion over Authority Gradient

SKYbrary notes that, in some situations a shallow authority gradient may exist solely through the composition of the team and/or the type of task being conducted, rather than through an overly democratic leadership style.

Aircraft captains often fly with other captains. Flying trainers and examiners will fly with fully qualified pilots; sometimes, these trainers will be under observation themselves from another trainer. Safety auditors may be observing crew behaviours, yet be senior pilots themselves. Parallel situations also exist in air traffic control, maintenance and airport operations – where experienced personnel fulfill tasks for which they are over-qualified and supervisors, instructors, auditors and examiners may be observing or playing and active role. Similarly, a generally inexperienced team member may be highly valued for a specific skill, and even employed solely for this reason; other team members can then easily over-estimate this person’s capabilities through generalisation and association.

This problem can be found in the dynamic of governing boards. Headteachers, promoted for their ability to lead learning, may lack the business and commercial skills to lead effectively outside their original area of pedagogical expertise. Governors need to be aware that, in the final strategy-decision conversations, they are the decision makers.

On highly experienced, very qualified governing boards there is potential for confusion when some governors, aware that others of their number have experience of serving on other school governing bodies, may erroneously assume that, because those governors are silent on an issue, all must be well.

This confusion about role and ill-understood authority gradient may well have contributed to the catastrophic and very public collapse of the Kids Company charity. Within the organisation, a charismatic leader ruled as a larger-than-life figure. At board level, in spite of having strong and experienced board members, confusion over who was holding whom accountable led to the inevitable financial crash.

Whenever there is a lack of clarity in roles, responsibilities and capabilities, it is likely that decisions and actions will not be taken effectively; some team members may not participate when expected, and other team members may act independently towards different goals.

How does your school or academy trust deal with issues around the authority gradient? What action might you need to take so that you are speaking up before the airplane crashes rather than sitting in the co-pilot’s seat on the way to financial or regulatory disaster?